Americans are Not as Polarized as We Think

Americans agree on social and economic policy more often than is assumed

In 1950, the American Political Science Association (APSA) published a 99-page report urging the two major parties in America to become more centrally organized and nationally focused. The genesis of this report stemmed from the APSA’s concern that the parties did little to distinguish themselves and lacked an authoritative leadership structure that could provide clear and concise platforms.

Not all political scientists agreed with the report’s recommendations, but it represents a state of politics that is so foreign to us today. Seventy years ago the concern was the lack of polarization, today we exclaim there is too much. So much so that polarization has been credited with a substantial amount of blame for a decline in democratic performance, that is because, in a polarized nation, a party-controlling government has a greater incentive to take institutions designed to protect democratic norms and transform them into authoritarian instruments1.

Assessing the current state of polarization in America and its impact on voters is a complex undertaking due to the multitude of methods available for measuring polarization, each with its unique strengths and limitations. Moreover, polarization can be examined at two primary levels: among political elites, which pertains to politicians, and among the general electorate.

These two levels of analysis often yield different results. That is why in the following sections, I will explore polarization at both the elite and voter levels and examine possible reasons for variations between the two.

Polarization in Congress

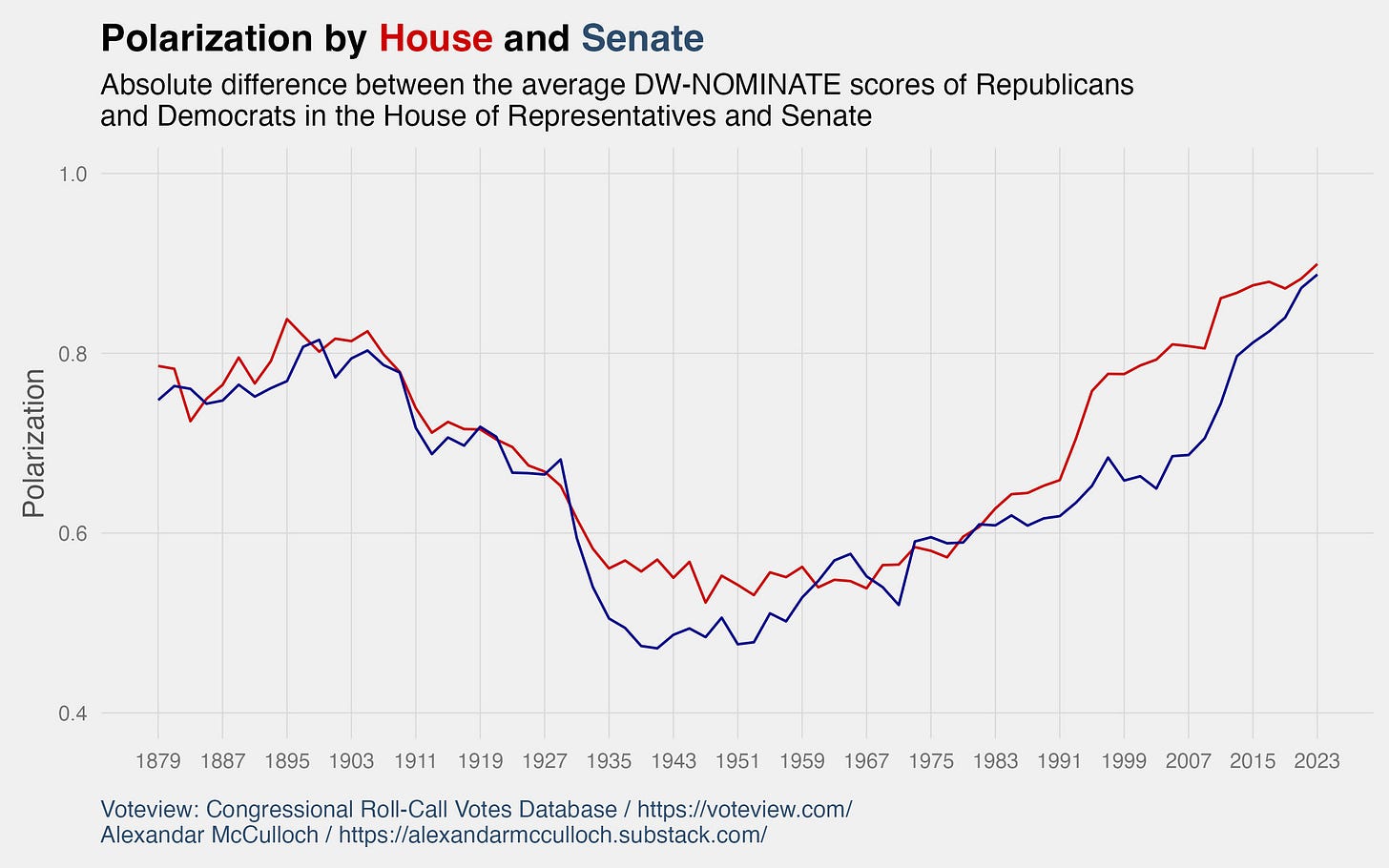

To gauge the extent of polarization in the United States, I rely on a valuable tool employed by political scientists – the DW-NOMINATE dataset. Developed by Keith Poole and Howard Rosenthal this dataset provides a means to quantify and track the ideological positions of members of Congress. These scores are calculated using votes cast by each member of Congress. Once these scores are obtained, we can calculate the rate of elite polarization by calculating the difference between the average scores of Republicans and Democrats.

The following two graphs illustrate the average nominate scores of Republicans, Northern Democrats, Democrats, and Southern Democrats in the House of Representatives and Senate. These scores reflect the liberal-conservative spectrum, ranging from -1 (most liberal) to 1 (most conservative).

Senate and House Republicans have exhibited a more rapid rightward shift compared to the gradual leftward movement of Democrats. We can see this increased rate of change begin in the late 1960s and continue through 2023.

This change in Republican ideology can be attributed to the civil rights movements of the 1960s and 1970s. However, we should be careful not to attribute the source of our growing polarization to the large shift within the Republican party. The causes and effects of polarization are complicated and our research on the subject is ongoing.

The graphs above show a clear trend of growing polarization at the elite level. However, politicians are not the most accurate portrayal of the average American. Yes, members of Congress are voted in by their constituents, however, that does not mean they adopt the same preferences as the average voter.

Polarization Among the Public

Shared Preferences

There is strong evidence to suggest the United States is not as polarized as most claim. Rather, the extreme polarization that is documented can be attributed to a specific group of individuals that represent ideologues and party activists.

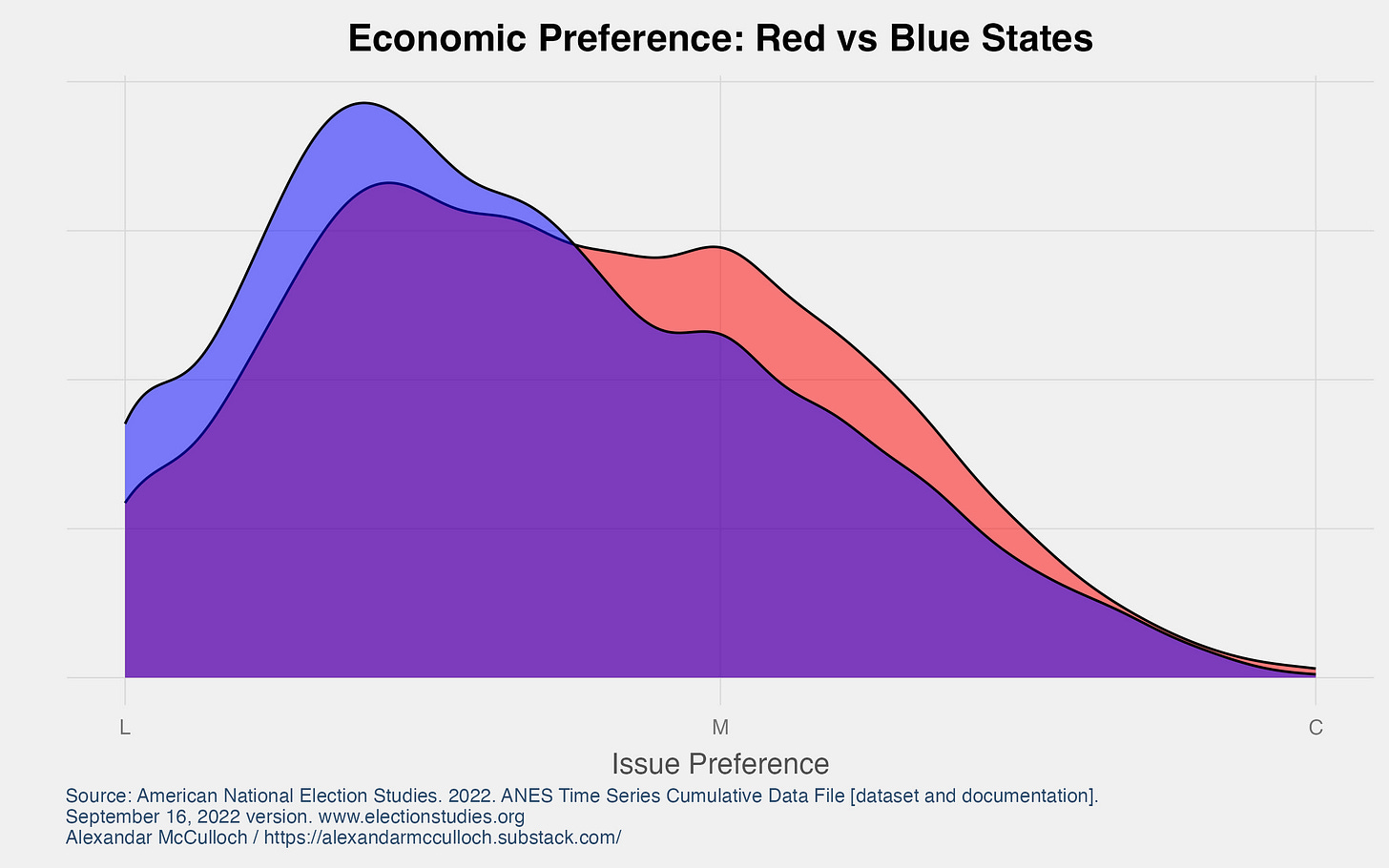

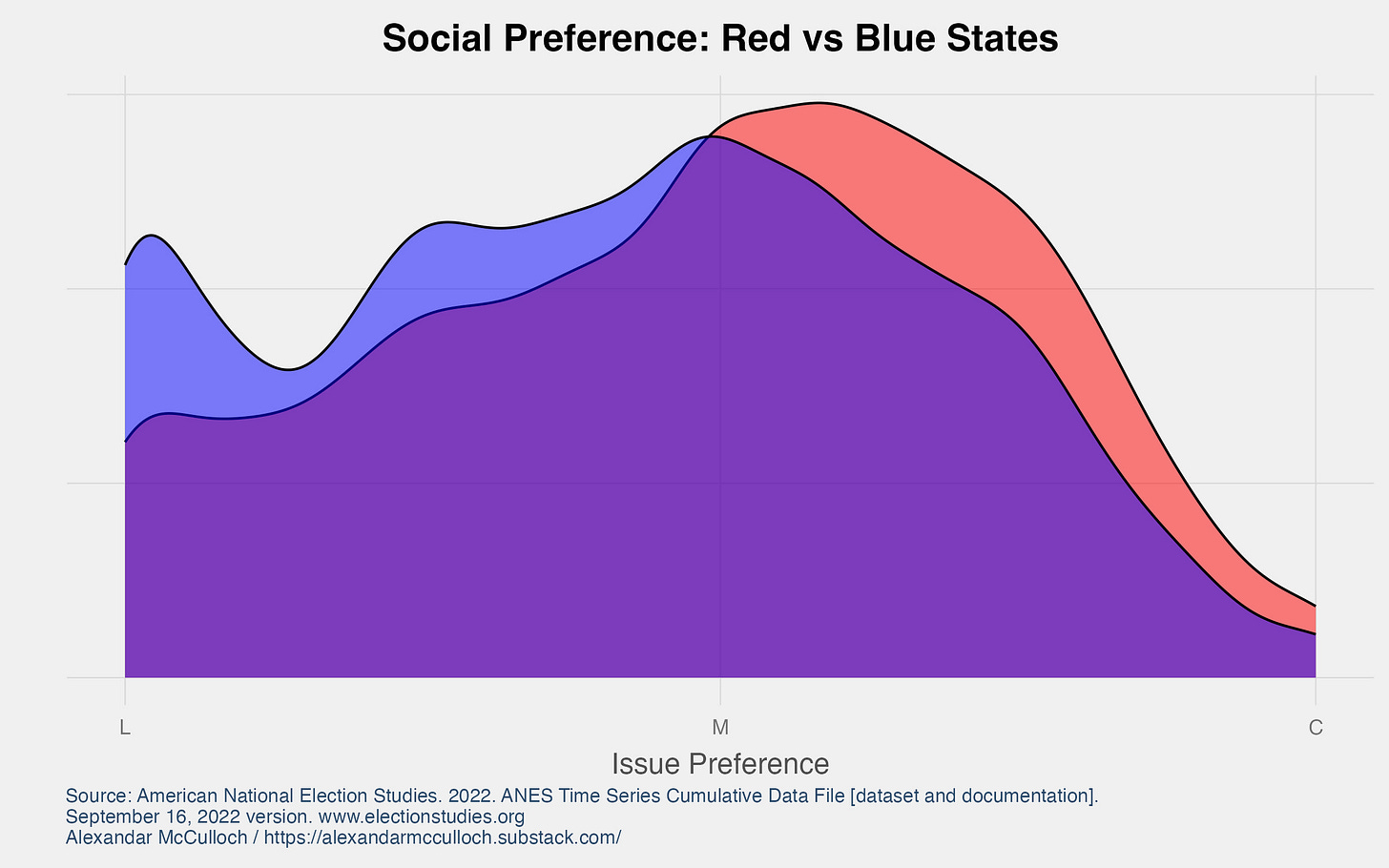

To gauge the level of polarization among voters, I replicate findings from Levendusky and Pope’s 2011 paper Red States vs. Blue States: Going Beyond the Mean2. It is typical for researchers to conduct a simple difference-in-differences (DiD) test to determine polarization. Indeed, the visuals from the previous section are the result of a DiD test.

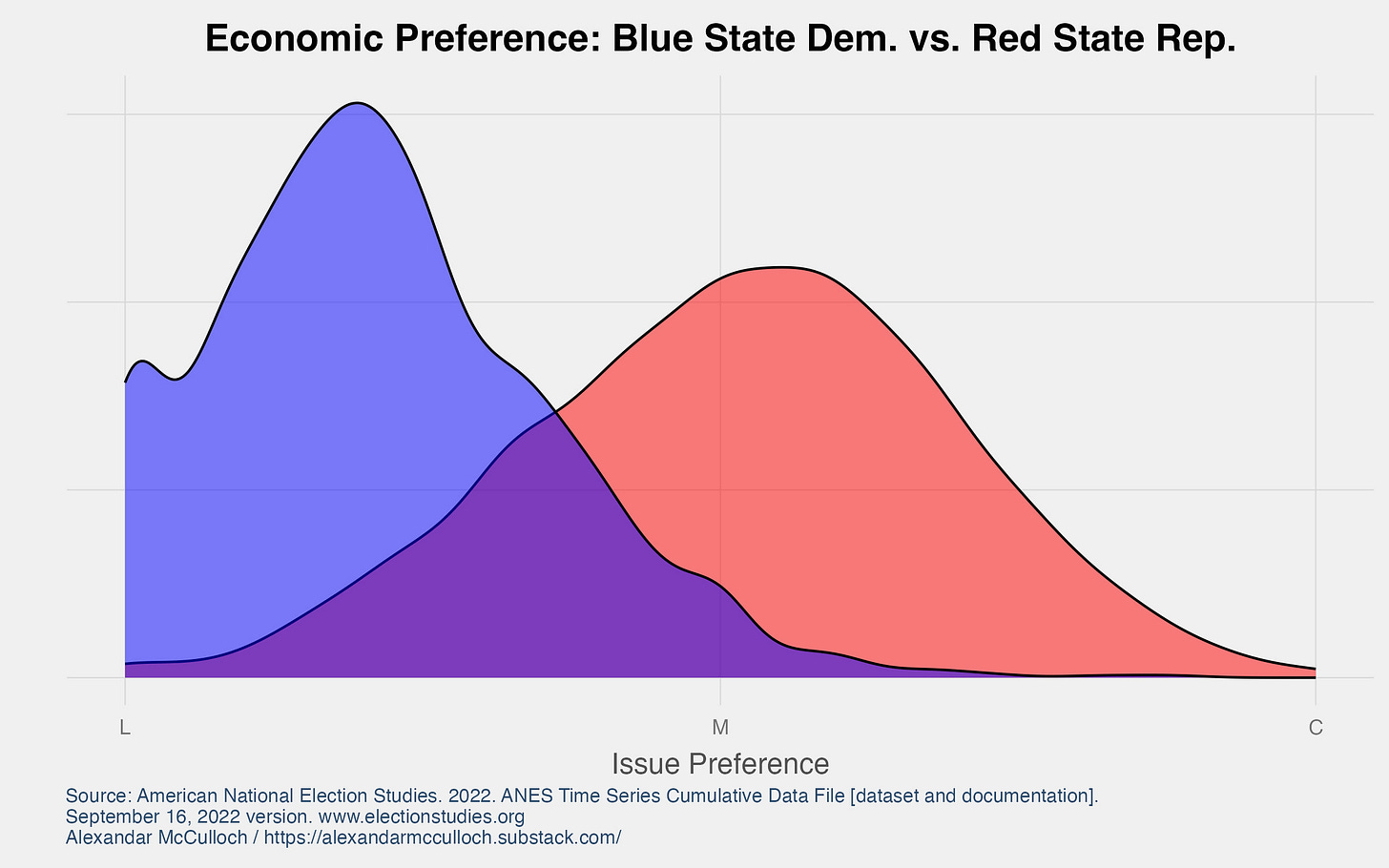

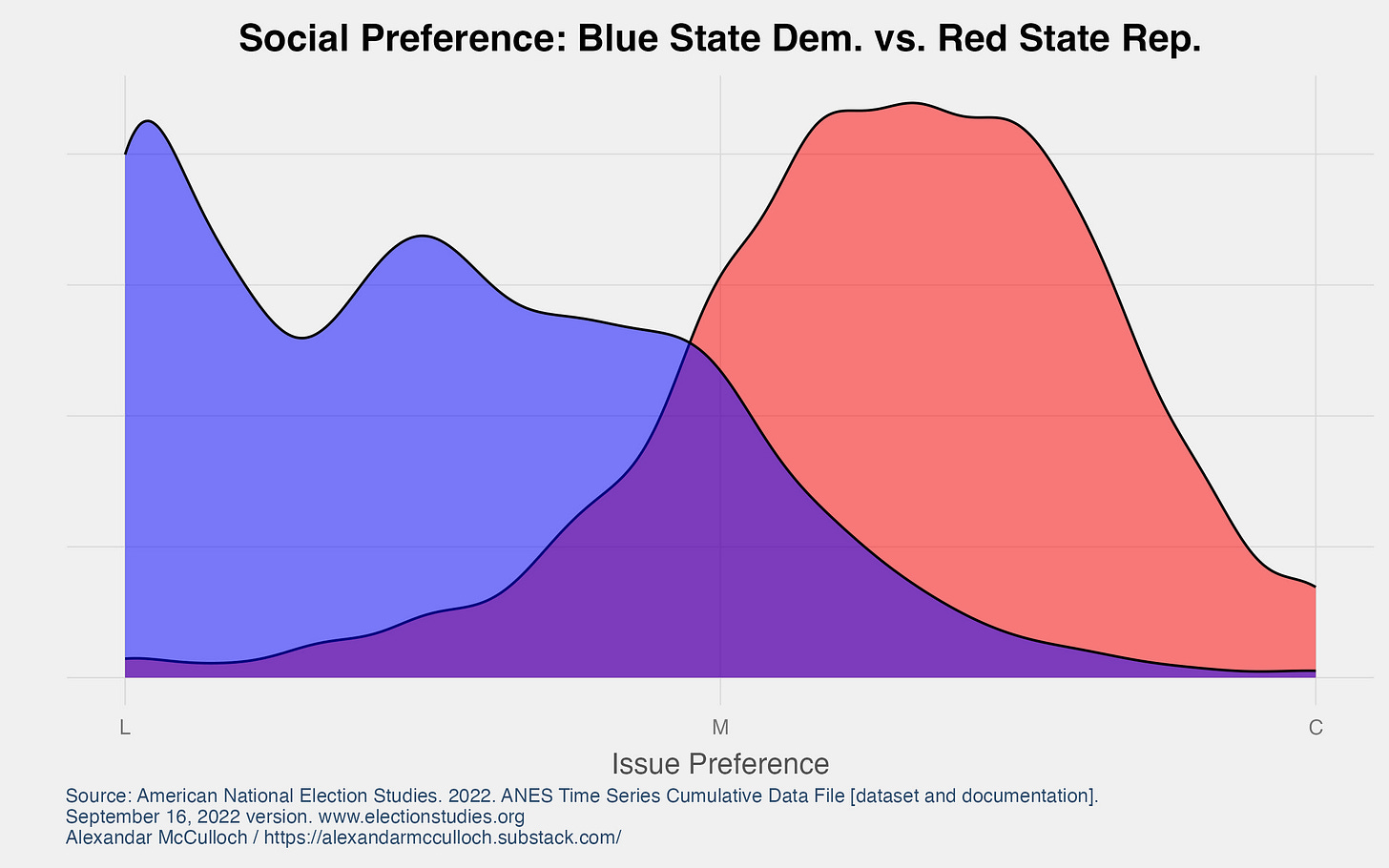

I can do the same test to determine the rate of polarization at the voter level, however, Levendusky and Pope offer an alternative. Rather than a simple difference in means, I pool all blue-state and red-state voters into two groups and plot the distribution of their policy preferences. By using density plots we can visualize the distribution of voters’ policy preferences along the liberal-conservative spectrum. The peaks and valleys of the curve indicate where data points are more or less concentrated. This way, we can not only view the unique preferences between the two groups, but also gauge the overlap, or shared preferences, between red- and blue-state voters.

I create two issue dimensions: economic and social3. These dimensions are defined by a collection of survey questions that measure respondents’ attitudes on issues such as spending, social security, abortion, immigration, and affirmative action.

What is striking about the graphs above is the remarkable level of overlap between red and blue states, with a 91% and 89% overlap in economic and social policy preferences, respectively. This suggests that the general public may not be as polarized as commonly assumed. In fact, these visuals indicate quite the opposite – the American public largely agrees on numerous issues spanning economic and social dimensions.

For a formal analysis, I calculate the probability that a random blue-state voter is more liberal than a random red-state voter. The results reveal that a blue-state resident is 55% more likely to hold liberal views on the economic dimension and 56% more likely to do so on the social dimension. While blue-state voters tend to lean more liberal than their red-state counterparts, the difference is roughly akin to a coin toss.

The evidence here suggests that red- and blue-state voters share similar preferences. Indeed, even blue states have conservatives and Republicans just as red states have liberals and Democrats. However, it’s essential to consider whether these visuals might obscure crucial information. The notion that the U.S. is not as polarized as commonly assumed raises the question of whether conventional wisdom is misrepresenting reality or if our tests fail to capture the full extent of this phenomenon.

Partisans tend to be more active and vocal than the average citizen. Therefore, the polarization we often identify might stem from the divisive rhetoric and actions taken by Democrats and Republicans themselves. This partisan divide may be better understood as a division within a specific subgroup rather than a divide between all voters.

The graphs below illustrate a more substantial divide between blue-state Democrats and red-state Republicans. While distinct from the previous visuals, these graphs clearly show a large overlap between Democrats and Republicans. The overlap between partisans on the economic dimension is 35% while the overlap for social policy stands at 48%.

After examining these graphs, one can still claim there is still polarization among the American electorate. That is not unreasonable, as polarization is inherent in politics. However, the polarization we observe can largely be characterized as partisan polarization – polarization driven by partisans, rather than average voters.

The high level of elite polarization begins to make sense as we observe higher levels of partisan polarization within the electorate. Partisans are more active, they participate in primaries and often hold opinions that are more extreme than their less active peers. Therefore, while we observe less polarization within the entire electorate compared to Congress, the Senators and Representatives who represent these voters most accurately reflect the values of the active voter rather than the passive one.

Voter Impact

Some argue that the perception of increased polarization is, in fact, a result of better partisan sorting.4 Partisan sorting involves the alignment of political party affiliation with ideological beliefs. This process leads to greater ideological homogeneity within political parties, such as Democrats becoming predominantly liberal and Republicans predominantly conservative.

This is distinct from the idea that the public and elected officials are adopting increasingly ideologically extreme and distinct policy positions. Evidence supports the existence of both a better-sorted electorate and a more polarized one. Regardless of one’s preferred interpretation, researchers are still able to identify specific consequences affecting the public.

Conflict Extension

Polarization’s growth has introduced voters to new challenges. One notable phenomenon is conflict extension5. Unlike the past, when parties primarily disagreed on a few major policy areas like slavery, civil rights, and the New Deal, contemporary polarization spans almost every policy domain. For instance, someone who takes a liberal stance on LGBTQ issues is now more likely to also hold liberal positions on topics such as abortion, gun control, taxation, and environmental regulation. The range of issues over which the two major parties clash has significantly expanded.

The question here becomes, who is leading this process? Evidence suggests that party activists are the engine behind this movement. This is for reasons I previously stated. Activists are more likely to harbor ideologically extreme positions and introduce new salient issues to the party.

Furthermore, changes to the party system have made the party more accessible to activists. Barriers have dropped since the 1960s, which makes this one contribution to the increasingly polarized climate.

Affective Politics

Partisan affiliations not only shape our political beliefs but also impact our emotional reactions toward our political adversaries6. As people become better sorted, they tend to exhibit more bias, and experience heightened emotional fluctuations. Those with strong partisan identities not only display hostility toward those outside their group but are also driven toward political activism. This phenomenon operates independently of one’s actual policy positions. Political parties start resembling one’s favorite sports team, motivating voters to become more engaged, not necessarily to promote specific policies, but rather for their team to win or the opposition to lose.

Furthermore, as one social group clashes with another, our group’s identity takes on a central role in defining their individual identity. Consequently, as partisan competition intensifies, citizens tend to approach politics more as Democrats and Republicans rather than as American voters.

This confrontational approach to politics can give the impression that we are more polarized on issues than we truly are. This is because we can visibly perceive and feel a growing social polarization, which is expanding at a faster rate than polarization based on policy positions.

The current state of American polarization is a complex and multifaceted phenomenon. The nation’s political landscape is undeniably more polarized than it was at the publication of the APSA’s report. The historical context reveals a stark transformation from a concern about the lack of polarization to the contemporary alarm of its excess.

The concern today refers to social polarization more than issue-based polarization. As our identities become consumed by our political ones, we become more concerned with our side winning. As ideology and partisanship converge, voters are driven to activism, the group primarily responsible for the growing polarization observed in Congress and the overall issue-based polarization across the country.

Liberman, Robert C., Suzanne Mettler, Thomas B. Pepinsky, Kenneth M. Roberts, and Richard Valelly. 2019. “The Trump Presidency and American Democracy: A Historical and Comparative Analysis.” Perspectives on Politics 17 (2): 470-79.

Levendusky, Matthew S. and Jeremy Pope. 2011. “Red States Vs. Blue States: Going Beyond the Mean.” Public Opinion Quarterly 75 (2): 227-48.

Matthew Levendusky. 2009. “The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republicans.” University of Chicago Press.

Carsey, Thomas, and Geoffrey Layman. 2015. “Our Politics is Polarized on More Issues than Ever Before.” In Political Polarization in American Politics, ed, Daniel J. Hopkins and John Sides. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 23-31

Lilliana Mason. 2015. “ ‘I Disrespectfully Agree’': The Differential Effects of Partisan Sorting on Social and Issue Polarization.” American Journal of Political Science, (59) 1: 128-45.